3 Hopes and Dreams

3.1 Hobbies

My own children grew up in a world with screens everywhere, and it’s hard for them to understand a place without the TV or internet. What was there to do?

Plenty! Our lives were a rush of school and church activities, a big woods nearby that needed exploring, and an unlimited number of hobbies. Surrounded by the natural world, we collected rocks for polishing, and I remember keeping small potted plants – a tiny cactus. Gary had an Erector Set and I had Tinker Toys. Like all girls her age, Connie had her Barbies.

Stamp collecting came naturally in a preacher’s family that occasionally received letters from missionaries in other countries. Paper letters were natural and abundant in those days, and so was were the stamps affixed to them. Competition was natural for two boys so close in age, and my brother generally avoided direct matches with me, so I think he wasn’t particularly serious about his stamp collection, and appeared unconcerned that mine seemed to be always bigger and better.

Then one day, out of nowhere, a package arrived for him containing a treasure of philatelic supplies: genuine stamps from around the world, a book describing how to excel at the hobby, and a magnifying glass. He was elated! Somewhat enviously, I agreed to look more closely at his new haul, when I noticed the fine print on the cover letter, explaining that this package was being sent on a trial basis by generous people who just knew that he would want to purchase it, but that in the very unlikely chance that it didn’t meet all his desires, he was welcome to return it without charge.

Naturally he was devastated. Now I know that such unsolicited mailings are illegal and that he would have been entirely within his rights to keep the whole package, but at the time it was nothing but a letdown and his interest in stamp-collecting disappeared.

That’s okay, because we had plenty of other ways to keep busy. We played with model rocketry and model airplanes, loved by my brother, who was always more of a builder than I was. And of course there was music.

3.2 Music

We didn’t think of ourselves as an especially musical family, though by most standards today I guess we were.

My mother had a good singing voice, but had never learned to read music or play an instrument, so most of the musical activity in our family came from our father, who learned from his grandmother. We had a piano in our home, I think as a gift from Dad’s family, and he would often in a moment of boredom play a few pieces from memory, like the hymn “When I think of the goodness of Jesus”. He whistled too, and it was not unusual to hear him humming a song or two. I think he secretly wished our family was much more more musical. He sometimes referred enviously to families that would sing together on long car rides (though sadly, to even mention this out loud to my siblings would have brought groans), and we owned a stereo phonograph, a luxury for a family with little spare cash.

From an early age, then, all three of us kids were expected to learn music.

Any potential talent on my part was apparently not visible when I was in kindergarten. My teacher was disappointed in my singing voice enough that she singled me out among my classmates for special training by a special education teacher. Once a week I was led away from the class to meetings with a woman who gave me singing exercises. At the time I thought it was silly and pointless: she asked me to tap along with a time signature for example, or sing simple “do-ray-mi” scales. I must have done okay, though, because I was rewarded after each session with a piece of candy which, ironically, I didn’t like and promptly passed along to a classmate.

My brother and I began piano lessons early, at first taught by Dad, but soon taught by an elderly lady down the street. She gave each of us a practice card in which we were expected to record the number of minutes each day that we practiced. If the totals were not at least 20 minutes per day, we knew we’d suffer from her stern looks and reprimand at our next lesson.

I don’t remember being especially diligent one way or another, but I do remember being surprised at my brother’s struggles. Concepts that seemed easy or obvious to me seemed to take him extra time to master. Since until then I had always assumed that my brother, being older, was naturally better than me at everything, this was the first time it occurred to me that maybe I could outcompete him at something.

In third or fourth grade, our elementary school began to introduce interested students to instruments and my brother and I were encouraged to think of which we’d like to play. He chose the alto saxophone, for a reason I no longer remember, and soon our house was full of the struggling sounds of a beginning saxophone player. He seemed to enjoy it, and I couldn’t wait my turn to learn an instrument as well.

Somehow I was intrigued by the fife and drum photos I saw in paintings of the American Revolution: I chose drums.

Our music teacher, Mr. Rasmussen, explained that the percussion section was the most difficult in the orchestra and that only those students who performed highest on the music test would be admitted. My friend Todd Makie made the cut, but I did not. The rejection disappointed me, though I assume my mother was secretly relieved that our house would not be filled with the noises of an aspiring drummer. And thus I became a flute player.

A year later, it was Connie’s turn to choose an instrument and somehow she chose the trumpet. If you had passed by our house that year, on any given day your ears would have been confronted with the off-tune sounds of three kids, dutifully practicing our mandatory minimum of twenty minutes a day. And for many years of Sunday mornings after that, any visitor to our church would have heard our orchestra in the front: the three Sprague children plus the Gungors and a few others playing in the song service.

I didn’t know at the time that the flute was a “girl’s” instrument and it was several years before I noticed that I was the only boy flautist in the band. Despite the normal awkwardness of any teenager pressured to conform, I don’t remember ever regretting my choice. In fact, I appreciated the many advantages of a flute compared to other instruments: its size makes it much easier to carry and cheaper too. Unlike reed instruments like my brother’s saxophone, there are no consumables. I also liked the smooth, simple sounds and the range. The result was that I found the flute enjoyable to play, and I practiced enough to become the best in the school.

In our regular competitions, I always placed first, advancing to regionals and finally to win at the state contests too.

Well, that’s not quite true. I wasn’t always first. Each year, our high school band held auditions to determine the seating arrangement for each instrument section. We were each given a set piece to play into a tape recorder, which would then be blindly evaluated later by the teacher for ranking. Somehow I came under the impression that the point of the audition was to see who could play the piece fastest. I practiced and practiced until I got my time under some unbelievably quick number of seconds.

Thinking there was no way my rapid performance couldn’t have been best, imagine my disappointment when the final seating chart showed I was among the last – sixth out of eight. Upon discovering my error, I asked the teacher if I could try my audition again. The rules were fixed, he said, so I would be stuck in my seat … unless, he added, I went through a process of challenging my superior seat-holder.

A “challenge” meant that I would formally invite a higher seat holder to undergo another recorded audition, where each of us would play a piece to be evaluated blindly by the teacher. Whoever wins that competition would take the higher seat.

And thus I systematically challenged my way from sixth place to first, in a process that must have taken weeks. But I never lost my first place again.

Gary too did well at these contests and he continued to play regularly through high school, when he joined our jazz band. As the lead alto saxophonist, he played weekly at sports games throughout the year, developing a reputation as a solid, reliable performer. Like me and Connie, he practiced regularly throughout the year to avoid disappointing Mr. Rasmussen in our regular music lessons.

We didn’t think of music as anything special – it was just something our family did.

Much later, upon entering college I auditioned for a place in the Stanford orchestra. The judge asked me the name of my teacher. Mr. Rasmussen was hardly famous enough for that, and I wondered why they bothered to ask. “You play remarkably well for never having had a teacher”, he said.

3.3 Our New House

For most of my childhood we lived in an old two-story house on Oak Street, a few blocks from church. This was the neighborhood near the Gungors and many other kids our age, with whom we enjoyed countless hours of play after school and in the summers.

Our house was owned and paid for by the church, a perk that partially substituted for the low income my father earned as a pastor. But as his family grew older, Dad began to think about his long-term future, including eventual retirement. Where would he live when, inevitably, he became too old to work?

The church board came up with a solution that resulted in a purchase of new property on the other side of town, and the construction of a brand new house that we would now own. One result of this delightful opportunity is that we were able to design the entire place from scratch. We were given catalogs of standardized floor plans, which we devoured as we speculated about the layout of rooms and hallways.

We contracted with a builder from church who, I’m sure, did the construction for close to his costs. He was also a skillful and flexible builder who knew how to build the house exactly how we wanted, regardless of whatever blueprints we found in the catalog.

During the more than a dozen years I shared a room with my brother, I don’t remember any particular conflicts. It annoyed me that he got to keep the top bunk, no matter how much I pleaded with him (and our parents) to swap places now and then. The lack of privacy, I’m sure, became more noticeable as we grew older, but to us at the time it was just normal. Neither of us could conceive of a different living situation.

That changed when we moved to the new house. For the first time, we could keep different hours. If either of us left something on the desk or floor, the other wouldn’t be inconvenienced. Instead of keeping my personal items in a box in a shared closet, I’d have a closet of my own.

There were many other changes. In our old house, the family shared a single bathroom on the upper floor. Now we would have two. We were no longer limited to baths; we could take showers. Instead of oil-powered heating, Dad arranged for us to have a wood-burning furnace, augmented with natural gas and electric. And of course, the kitchen appliances and bathroom fixtures would all be brand new.

This transition happened at precisely the right time, just before the inevitable changes in adolescence and high school threatened escalating conflicts with my brother. Now, for the first time, we would each have our own space.

3.4 Earning money

Although I never felt poor, money was always something my family needed to watch carefully. Later I would hear about truly poor families, those who had to go light on food at the end of the month, and I couldn’t relate because it never seemed that food, of all things, would be something to be rationed. In the middle of farm country, there was never a shortage of fresh food; people gave us stuff, not because they thought we needed it, but because there was so much extra that it made sense to share.

Still, money was not the type of thing to be given to children without a specific purpose – school lunch money, for example – so if there was a purchase we wanted, we needed to find our own money. Christmas and birthdays were one source, but for real freedom we knew we had to earn it ourselves. Fortunately, this was easy to anyone willing to work for it.

My brother was the first to find his own income. Mr. Swenson, an older man in our neighborhood, ran the newspaper delivery services for Neillsville and Gary became the delivery boy for a paper route. It paid by the delivery – on the order of a few cents per newspaper per day – but once you accumulated a few dozen customers, as he did, and were willing to work six or seven days a week, the income easily surpassed whatever any of us could expect from gifts.

As soon as another route opened in our neighborhood, I grabbed the chance too. My route wasn’t as many customers as my brother’s, but it was still good pay as far as I was concerned. Over time, between us we accumulated additional customers as other neighborhood paper boys grew older and dropped out, leaving the routes to us. Later an even bigger opportunity came, to deliver a weekly free classifieds paper (“The Shopper”). We had to deliver to every house, and this time we were paid by the insert as well, which came as a separate pile of papers and needed to be added to each paper before delivery. It was boring, manual labor but I learned to see every one of those papers, not as a tedious chore, but as income: a tiny downpayment on bigger and better things.

A paper route requires getting up early in the morning, every single day, good weather and bad. We had to be responsible, not only for delivering the papers in good condition to each household, but for collecting and tracking the money from subscribers. If we wanted more money, we could also walk the neighborhood door-to-door and find more subscribers, a sales job that I hated, but was absolutely part of the business.

Besides carrying newspapers, as we became older we found other jobs in the neighborhood: raking leaves, shoveling snow, mowing lawns, and occasionally a more substantial offer for another labor-intensive job cleaning a field or something. None of these jobs was particularly well-paying, certainly not by today’s standards, but it was real money and I learned to pay attention to every penny.

Although there were minimum wage and other laws, such legal technicalities were irrelevant to our job-by-job work. Our payments came in cash, without deductions for taxes or fees. We didn’t report anything to the IRS – we didn’t even know how – and if anything the idea of submitting a tax form would have filled us with pride, something to prove our adulthood.

We learned about earning income this way from my father, who also worked odd jobs. His meager pastor’s salary, less than $1,000 per month in 1970s money, was barely enough to live on, so he supplemented it with whatever extra money he could find. When I was younger, he roofed houses – a hot, backbreaking, and often dangerous job that he rarely did without a partner. Later, and more regularly he would paint houses, and sometimes I would go to the site with him, mostly to watch (apparently my mother believed the job was too dangerous for a young boy).

Our father earned his main side income in the woods. Rural Wisconsin, with its abundant forests, has long been a land of loggers. Paper mills were always ready to buy cut timber, and the men of my family had several generations’ experience cutting trees. I think my father was born with a chainsaw in his hands, and throughout his life few things gave him more pleasure than the sight of large trees ready to be harvested.

Throughout our childhood, he teamed up with another pastor, his best friend, who lived in a nearby small town. They found work subcontracting for a local logger who had the big tree-moving equipment, a “skidder”, and contracts with paper mills to deliver the logs, each of which had to be carefully cut into eight-foot segments, called “sticks”, with the bark removed. Removing bark (“peeling”) was a tough job, but it wasn’t especially dangerous for kids, so my brother and I were quickly enlisted. I worked in the woods with my father most of the summers of my childhood, right up to the final year before I left for college.

Dad cut the trees and then paid us by the “stick”, a six-foot measurement. When we were too young to peel, he recruited us to measure out the logs as he sliced the fallen tree trunk. As we grew older, we were given our own hand-sized crowbars to peel the bark and pile the logs for later skidding.

Each stick was worth five cents, and a reasonably strong and ambitious kid could do several dozen per hour, perhaps ending an eight-hour workday with several hundred sticks, or ten or twenty dollars, perhaps up to one hundred dollars per week. Older kids, once they mastered a chainsaw for themselves, could earn much more. For small town kids, without job possibilities at fast food or other service establishments, this was great money.

The work was very unpleasant. Getting to the worksite often required a significant hike through the woods – usually through thick brush, along clearings from previously-harvested trees. Mosquitoes and big, evil horse flies were a constant menace, made even more annoying while sweating in the hot sun. But the worst insect of all was the wood tick, a small creature that liked to burrow into clothing, then skin and could be difficult to remove. You wouldn’t find them until arriving home, by which time they had already begun sucking blood, leaving large itchy welts that persisted for days afterwards.

We cut the trees with gas-powered chainsaws so noisy that Dad issued each of us earmuffs to protect our hearing. The gasoline that had to be hauled into the woods as well, in large cans, and cans of oil too for lubricant. I was too young to touch the saws, but I’m sure Dad brought repair equipment as well. He carried two saws, and probably extra chains, to prepare for inevitable breakdowns.

Tree-cutting was itself as much of an art as a science, a skill my father developed with long experience judging wind conditions and the location of nearby trees. In a thick woods, there was a trick to deciding which trees to cut first: make sure they fall in the right direction and leave holes in the forest to make it easier to fell succeeding trees. A botched job of cutting one tree could increase the danger in cutting the next, because a tree that fell into another would now require a second tree to be cut, and possibly others after that, like dominos, each hanging dangerously high in the forest, potentially all collapsing at once on the helpless loggers below.

That my father did this successfully year and year out, was as much due to luck as to his long experience and apparent enjoyment in the work. When we pleaded him to slow down, or to take a few days off, he told us that his own father – my grandfather – had been an even harder worker.

The dangerous work produced its share of minor injuries: usually welts from branches that slapped into us unexpectedly, or cuts from peeling bark in places that were difficult to reach. Once, when I was in third or fourth grade, Dad had a serious accident: a deep chainsaw cut into his knee that required a doctor’s attention and long weeks of recuperation.

It was hard work, but monotonous, so to pass the time I began to amuse myself with a game that I played in my imagination. A “stick”, I imagined, was a year of my life – more precisely, the life of a fictional hero of mine. At age one – the first stick – perhaps something happened with his parents. At age two or three – the following sticks – came the first signs of precociousness, an inchoate musical ability breaking forth. Soon, as the sticks piled on, he was my age and quickly proceeding through school, skipping grades far faster than his peers, until by twenty he was out of college, on to a PhD, and further, farther in his career.

I don’t remember the details of my game, but besides driving away the monotony, I learned to look forward to these daily imaginations of the future. My hero would get older, wiser, richer, marry and have children, make fantastic accomplishments, each day better than the previous one. I was not nearly as fast or efficient a worker as, say, my brother who would routinely rack up a few hundred sticks a day. To me, reaching a hundred was a big milestone, rarely met by the end of the long day, which was just as well, since it kept me from needing to confront the mortality of my imagined hero figure, but just leave him comfortably into an old age while I thought about the money I’d collected that day and looked forward to even more the next.

The Neillsville Foundry

Our house was located at the outskirts of town, the very last house, separated by a field from a small steel foundry that provided good employment for hundreds of low-skilled workers in the area. One Spring day, my brother was asked if he’d like a job there too, for the summer. Since he already had a good position at the grocery store, he passed the information along to me and I eagerly accepted. So began my first major experience with the world of blue collar labor.

The foundry produced small metal objects, but to be honest, I don’t really know exactly. Perhaps it made parts for the other blue collar employer in Neillsville, the Nelson Muffler plant on the other side of town. Or maybe the objects were simply finished manufactured products useful for their own sake. Who knows. I only remember seeing the large steel smelting facility inside, and lots of metal molds in large sand pits.

I was hired to help dig out some of those sand pits, which apparently needed some attention after years of usage. There were other odd jobs around the factory too, like a field that was overrun with junk, and ancient supply rooms that needed clearing and sorting. Somebody in the factory had decided these tasks were perfect for some summer employees, and I – plus a half dozen other workers – became one of them.

I say half-a-dozen, because I vaguely remember there being several of us, but the only two I remember well were the person assigned to us as a “foreman” and a fellow classmate named Mark Dayton.

The foreman was the son of the town dentist, the older brother of a fellow student of mine. He himself was a student at UW Eau Claire, intending to be a dentist himself someday. This job was, to him, simply a way to earn some cash for college and expenses. This alone made him different from most of the other older workers, nearly all of whom thought of this factory as a career.

Mark Dayton was one of these. He got the job thanks to his older brother, who had been working at the factory for a number of years after leaving the army. Mark had no plans for college, and no real plans for what to do after high school, which was itself something he thought of as a parking place for himself until he left home and got a “real job”. He wasn’t a particularly good student, so I don’t think he would have minded dropping out of school entirely, if he had a permanent job offer from a place like this factory.

Mark and I became good friends. The work was lousy, lots of digging, lots of lifting; but there were breaks and frequent opportunities to talk, and it was natural for the two of us to spend our time that way.

One day Mark came to work with an announcement for me.

“I started something yesterday,” he said, proudly. The night before, in discussion with his parents, he had decided to pick up smoking. He showed me a new pack of cigarettes.

“Mom wants me to smoke the same brand as the rest of the family,” he said, “but I’m going to smoke Marlboros for a while instead. If I’m going to smoke, I want to taste something.” He said this in a matter-of-fact way, like somebody discussing the reasons for buying a specific brand of toothpaste or choosing a candy bar.

He wondered why I didn’t smoke – at least a few puffs now and then – and I tried to explain that I was concerned about lung cancer or other ailments. Of course, working as we were inside a filthy, smoke-filled factory, one where the management felt compelled to offer us face masks – it was hard to argue from a purely medical standpoint that cigarette smoking was a particularly bad habit.

He and many others at the factory offered me cigarettes, but when I refused, they never asked me again. I believed smoking was sinful, a violation of the Biblical commandment to treat the body as the “temple of the Lord”, a place never to be deliberately defaced. I realized even at the time that this commandment was subject to interpretation: we drank coffee and tea – hardly examples of healthy beverages – and for that matter, what about chocolate cake? Both of my grandfathers used tobacco – my paternal grandfather’s car perennially smelled of cigarettes, and my maternal grandfather enjoyed snuff—so I don’t think we were against smoking for any serious Biblical reasons as much as the simple fact that it seemed an expensive, wasteful, and generally unhygienic habit.

Even without cigarettes, I’m pretty sure that summer caused some strain on my lungs. We were issued face masks on the particularly dirty days, but even then, it seemed by the end of the day that every pore in my body was filthy. The pits we had to clean out were full of a fine sandy substance. Some of the pits seemed to have a different type of sand than the others; one in particular had a foul odor that I still remember. Even when I had been away from the factory for several days, I’d still find bits of this sandy powder coming out of my ears, or emerging from my nose. It was awful.

As awful as the labor was, on the other hand, the weekly paychecks were wonderful. Even after the various deductions (what is FICA anyway?), the total was more than months of delivering papers or mowing lawns. It felt like real money, too, earned through an official “job”, like a grownup. In those days, the odd jobs or the money earned from helping my father cut wood, didn’t feel as “real” for some reason. To be a serious job, you needed an hourly wage at a significant business, and for all its faults, the factory was definitely significant.

I had a goal in mind for the money I was earning: I wanted an Apple II personal computer. I had already carefully studied the prices and specifications, and the model I wanted was going to cost a bit over $1,000 including the color TV needed for a display. The purchase was well within my summer’s budget from my factory salary, and every day at the factory brought me a bit closer to my dream.

But just as suddenly as the offer had arrived at the beginning of the summer, the foreman one day made another announcement: our positions were being eliminated. I was laid off.

Suddenly, my dreams of saving money for the summer were shattered.

Odd Jobs

During the summer before my senior year, my father suggested we take advantage of the large empty field next to our house and grow a cash crop. Word at the time was that cucumbers were the way to go, so when Spring came, Dad found somebody with a tractor who tilled the field and made it ready for planting. We bought seeds and dutifully planted half an acre of cucumbers.

Agriculture is not an easy occupation, but somehow I ignored my father’s warnings about the importance of regular weed control and irrigation. The plants took longer to grow than expected, and by the end of the summer had produced far less than it would take to break even on our investment.

Cucumbers are sold to a distributor in town, who paid based on the size of the vegetables. Our field produced maybe one or two large sacks of cucumbers, but most of them were tiny and worth little. I remember bringing them to the distributor’s place and one-by-one inserting our crop into specially-measured holes, after which our results would be weighed. I no longer remember how much cash he gave us – perhaps $50 – but it wasn’t nearly enough to make up for all the trouble it took that summer.

Technically I was supposed to repay my father for the upfront costs of seed, fertilizer and the cost of tilling the field, but he had pity on me and let me keep the entire pitiful amount.

It takes a few years of growing before your crop starts to be profitable, he explained, a potential future that didn’t matter to me. I intended to leave town long before the next crop anyway.

Real Jobs

Despite our family’s history with family farming and the fundamentally entrepreneurial outlook that brings, I grew up thinking that “real” money came from a job with an employer and a steady paycheck. In Neillsville, as it is today for many teenagers, those jobs were in retail.

The ideal place to work was at the one fast food restaurant in town, the A&W root beer stand. The older, prettiest girls in high school seemed to get hired there, along with the best-looking guys who followed them. Although I supposed we Spragues might have liked to work there, it seemed like too much of a reach, so we never bothered to consider that as an option.

The town gas station was a more likely option. Before the oil crises of the 1970s precipitated the regulatory changes that allowed self-serve gasoline, boys were needed to pump gas. I knew an older boy who had worked there, but I was too shy to ask him about the process for finding a job there.

My brother was bolder. When, around age 16, he got serious about finding a part-time job, he approached all the places that seemed likely to hire. The gas station had no open spots, but Gary found more luck at our grocery store.

Neillsville had always had several small grocery stores, the largest of and oldest of which was a supermarket called the Neillsville IGA. Sometime when I was in elementary school, the IGA came under the ownership of Bob Solberg, who had begun his career operating a tiny competing dry goods store down the street from our house. We knew him partly through his daughters, Lisa (my grade) and Kim (Gary’s grade). Bob had a reputation as a hard-working, honest, and no-nonsense business man. Gary was a perfect fit.

He started as a stock boy, patiently moving boxes from delivery trucks on to the store shelves. He did other miscellaneous chores, from setting up new counters to cleaning floors and bathrooms. Eventually he worked his way up to the ultimate job: cashier. It wasn’t long till he developed a reputation as a reliable, hard-working employee who could be counted on to do anything, including the less fun jobs that other temporary workers avoided.

Years later, when Bob looked back on the hundreds of employees he’d hired, he remembered Gary as the best of all. Always on time, reliable, focused on completing the necessary tasks rather than simply punching the clock.

The job paid well by Neillsville standards, and for a high school kid raised by frugal parents, Gary was soon saving lots of money and before long he had his own car, a boat, and eventually even had moved into an apartment of his own. By Neillsville standards – in fact, by any standards – he was doing quite well for himself.

3.5 What I want to be when I grow up

I was in about third grade, and my mother was talking about me to some adults. “Ricky likes jokes. I think he’s going to be a comedian when he grows up.”

“No, I’m not,” I said, apparently offended that I might be categorized in such lowly terms. “I like history.”

I’m not sure if I understood what it takes to be an historian, or even if such a thing existed, but it was a clue that I saw myself as a thinker, one who makes a living from his brain rather than his muscle.

The earliest record of what I would be was a note my mother put into one of those fill-in-the-blank scrapbook albums for babies. Alongside the yearly height and weight, and favorite foods, there was the question: “When I grow up I want to be…” and a helpful multiple choice set of answers. Instead of “fireman”, my mother circled the choice for “astronaut”. Of course, in those moon race days of the 1960s, such a dream would have been common for every kid, and I suppose I was probably similar, to the degree I bothered to think about it. But like most kids, I needed several more years before I could think about it for myself.

My multiple bouts of hospitalization, and experience of seeing Dr. Gungor’s position first hand, made me interested in becoming a doctor. That seemed like a good fit, and it matched my eagerness to learn about science, but it never became a passion. I just felt that, yeah, I could do it; it was good money and prestige, so why not.

Missionaries and Languages

Sometime in elementary school, maybe after fourth grade, after a world cultures reading when I learned about Saudi Arabia, I learned while in the midst of a fervent prayer session, that God wanted me to become a missionary. Saudi Arabia seemed like an especially challenging place, and that’s where I wanted to be. I didn’t know anything about what it would take to be a Christian missionary in a Muslim nation, but who was I to question God’s call? It just seemed obvious that this was why I was put on the earth, and for many years that was what I understood would be my life’s work.

Perhaps it was too obvious, too inevitable for me, so I didn’t pay much attention to the mechanics of what it really meant to be a missionary. Of course I needed to learn more about God, through prayer and Bible reading, but I was doing that anyway. The social studies classes at school, where we learned about other cultures, kept me interested in the idea of foreign lands, but I don’t remember taking it to a deeper level.

But around the same time, my schoolteacher showed us a documentary about linguistics that absolutely fascinated me. Although if somehow I were ever able to find that film and watch it again, I’m sure I would be disappointed – it has built up quite a monumental reputation in my recollections—but it instilled in me the idea of how interesting the mind is. Like the short story I read in third grade that exposed me to computers for the first time, I suddenly saw how language was another way to become smarter. I realized that I really wanted to learn another language.

Real missionaries visited our church from time to time, and when they did they usually stayed at our house for a few days. I remember missionaries who talked to us, over dinner, about places like Thailand, South America, the Philippines, South Africa. It gave me a sense that foreign countries were real places, with real people who were just like me only from a different culture. What was it like to speak another language, to think from a different culture, I wondered.

Like many Americans, another exposure to the rest of the world came from the friends and relatives who had served in the military. One such family, the sister of a regular church-goer and good friend, had just returned from living in Okinawa Japan, and had even brought a missionary back who presented at our church. The missionary visited us with his family, and I met for the first time somebody who had lived in Japan and – what really impressed me – had learned to speak some Japanese. I no longer remember the words they tried to teach me – I’m sure it was simple greetings or perhaps numbers – but the very sound of the words impressed me. How does language work, I wondered? How can you possibly express the same ideas, using completely different sounds and symbols?

I had other hints about how fascinating it would be to know another language. It was in the evening, at a church Bible study held at the home of one of our church members, and as was the custom each person was asked to read a verse from the Bible, one at a time, around the room. There was an older woman there, from the Chippewa Indian reservation, who apologized that, although she had brought her Bible, it was written in her native language so she would be giving an on-the-fly translation that might be slightly different wording. My father, delighted by this, asked her instead to read in her native language, and she did. At this point, the hosts of the Bible Study, who were immigrants from Germany, admitted that they too normally read the Bible in their own language. It struck me as absolutely amazing that, not only were there different words that meant the same thing, but that you could have a key idea from the Bible represented in a code that was perfectly intelligible only to those who understood the language.

All of this made me eager to learn a second language. Our school taught basic Spanish starting in middle school, and I tried as best as I could with the couple hours per week minimal exposure. But obviously I was not going to get very far and I lost interest. Spanish wasn’t my idea of a “great” language. Meanwhile, I noticed in my father’s collection of books a five-language dictionary: translations to/from English, Spanish, French, German, and Yiddish. It was great fun to look up words in one language and see how they sounded in another. Of course, since most of the words were indo-european, it wasn’t hard to notice the similarities, and this gave me more confidence in my ability to master these languages.

In Jimbo’s house, I found another interesting set of books, a course on memory from Dr. Bruno Furst. My father had the same book, a home correspondence course with tips for how to develop a perfect memory. I devoured the series of lessons, driven by the desire to reach one of the later ones “Learn a foreign language on the plane ride to the country”. When, at last, after surviving chapters about memorizing long phone numbers and people’s faces, I arrived at the one about languages, I learned again how similar the European languages were, and once again developed additional self-confidence that I too could someday be bilingual.

But why Spanish? I thought. Here my mother intervened in my life in one of the critical ways that made me what I am today. We needed to choose which classes to take among a set of electives that included two that I really wanted to try, home economics, and industrial arts, plus Spanish. I decided that because I already knew the basics of Spanish, I could skip it. But my mother wouldn’t let me. I was angry and disappointed at the time, but she insisted that I needed it for college. Ultimately I was able to take the other electives anyway, but her insistence that I take Spanish the whole way kept me focused on learning the language – any language – in a way that I couldn’t have had the self-discipline to do on my own.

Still, Spanish was never enough of a “cool” language for me to want to seriously devote myself to it. My teenage arrogance let me think I already knew the basics well enough – after all, hadn’t I studied the 5-language dictionary, didn’t I already know much of the simple vocabulary, wasn’t I learning the basics of the grammar?

Travel to Mexico, fortunately, forced me to confront my linguistic limitations. True fluency, I realized, would take more than a Dr. Furst course. But the American-born missionaries I met convinced me that it was achievable. Maybe I would try a different language, but I definitely wanted to know what fluency felt like.

3.6 Computers

I first became aware of computers through a reading assignment in third grade and I was hooked. The short reading, which described the fast math calculations possible on a 60’s-era minicomputer, made me excited about the possibilities of how much smarter I could be if I had one of these things.

Around that time, my father took a part-time job working for the county surveying office, and they issued him a pocket calculator. Although I’m sure these devices had been existence by then for a few years, it was an early (and expensive) model that we otherwise wouldn’t have been able to afford, and I was fascinated. Today we take calculators for granted – they’re so cheap and ubiquitous – but in those days it seemed like a work of genius. Not only could it give instant answers to any arithmetic operation – including division, which to my elementary school mind seemed impossibly complex – but it gave answers to eight digits of precision. This calculator was a simple four-function model, so it had no fancy scientific operations, but that made it all the more approachable to me and I remember spending hours playing with it, and imagining all the fun I could have if something like this was available to me all the time.

By middle school, calculators were becoming common enough and cheap enough for normal families to afford, and it soon was on the list of items I’d like to save up for and own for myself. My paper route money, accumulating slowly, was already enough to afford the cheapest models and in time I might be able to afford one of the real fancy ones.

My decision was made for me, or so I thought, when John came home with a new calculator. Oddly I no longer remember the details of what made is special: maybe it was solar-powered, or maybe it had some additional functions like square root, but I do remember explaining one day to my mother that this is the one I needed to buy.

“You can’t have it,” she said. “You’re just buying it because John has it.”

Mom understood that this was money that I had earned myself, and she must have wondered if it was better to simply let me squander it rather than assert her power to prevent me from a purchase with my own money. But she was also right: I didn’t need that particular, more expensive model. She was teaching me that in order to justify my purchase I needed a better explanation than simple peer pressure.

Ultimately I bought a slightly different model, a bit cheaper but just as good. Prices on electronics always go down, so my delay was to my advantage and I ended up with a pretty good model. I also learned a lesson about the importance of thinking for myself and making my own judgments. It helped that money always seemed tight, like something you had to measure and count carefully, never to be wasted. It was a good preview for the way the rest of my computer life unfolded.

Somehow during this time period, John had become interested in electronics. He found a mail-order company that sold kits, a bundle of parts and instructions that let you assemble your own device. He was good at it, and he began to make electronic equipment, first some simple ones, but was close to taking the biggest plunge and building a full-blown color TV set. Although it was well beyond my budget, I followed his activities closely and soon found myself in competition to understand more, not only about electronics generally but about new and interesting devices I could assemble for myself.

This led me to the discovery one day at the school library, of a magazine called Popular Electronics, and a rival and more technical one called Radio Electronics which in the mid-1970s began publishing more and more articles about digital electronics, including how to build primitive computers. To call it a “computer” these days would be considered an exaggeration: it did nothing more than simple computations – there was no keyboard or display. The key part was a CPU, which at about $18 was a lot of money to me, but not an impossibly-large sum. The trick was how to get ahold of the part.

Since the chip was made by RCA, I started with a local TV repair shop in Neillsville, asking the owner if he was able to order parts from RCA and to my delight he said yes, and that the particular CPU I wanted was something he could get for me. The final price tag, including charges for special ordering it, was just too much for me to take the plunge on just yet, so I passed, but it got me thinking a lot more about computers – and I began to scour every issue of Popular Electronics as soon as it arrived at the library each month.

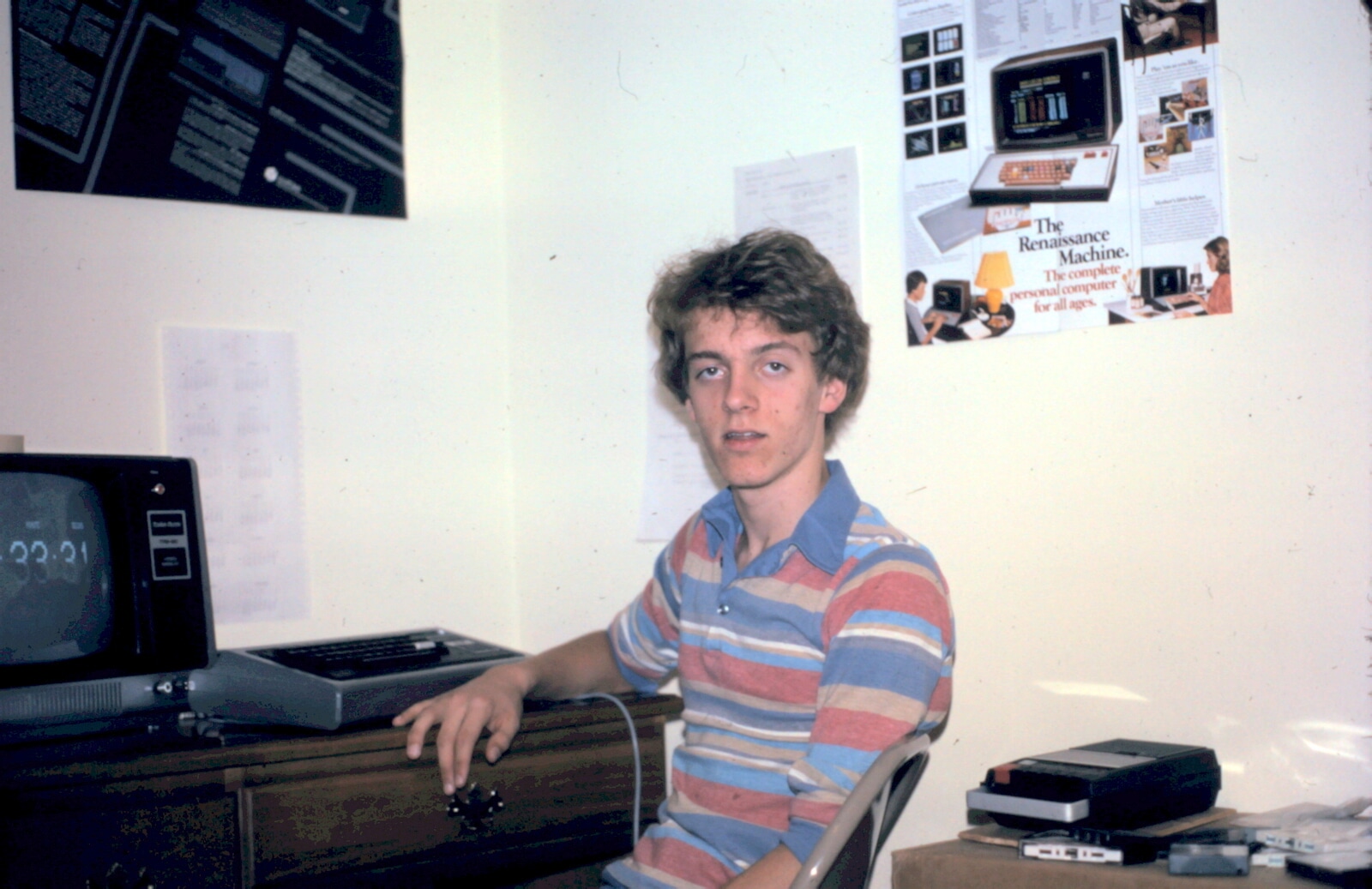

Our library also had older issues of these magazines and in my hunger for anything to learn about electronics, I discovered the January 1975 seminal cover story about the MITS Altair computer, now regarded as the first PC. I was absolutely floored that such a thing was possible, and I immediately wrote to the company for details and a price list. I still have the letter they sent in response, including a poster-sized description of their products which I hung on the wall of my room.

But getting my hands on a micro-computer would be expensive, far more than I was able to pay especially for something with so little practical use. Fortunately, around this time our high school library signed on to a new timeshare computer service from the University of Wisconsin River Falls, and I became hooked.

In today’s world, where computers are absolutely everywhere, a timeshare computer – literally, you “share” time with others on a single computer – seems crazy slow, and it was. The computer terminal, installed in the high school library, was a simple typewriter-style printer, connected to a central “mini-computer” a hundred miles away at state university extension. The connection, through a phone line, could send and receive characters at the rate of 100 bits per second, or roughly five or six characters per second each way. The terminal in our library wasn’t a computer—it was just a printer with a keyboard, and each keypress had to go through the phone lines to the computer, where it was carefully shared with the keystrokes of dozens of other users in a way that made it feel like a personal computer. Each keystroke was sent back through the phone line and printed on a long, continuous roll of paper, at which point you could type another key and the process would continue. A series of characters typed this way would constitute a command to tell the computer to do something, at which point it would then send back a stream of characters representing its answer.

Even such simple functionality, at the time, was probably outrageously expensive, but our high school justified the cost because it came with online information about careers and colleges. This database, plus a few other equally simple applications were enough to excite the staff of Neillsville High School, but John was excited about something else: the innocuous-looking programming manual that came with the terminal.

The computer could be programmed in BASIC, a simple coding language that was deceptively easy, even on such a slow terminal. John started by writing some very simple programs, and after he showed me how, I was hooked. Soon I had memorized the manual and was carefully crafting new programs in every spare moment I had.

The process was painfully frustrating: I would write my program at home, without a computer, and then enter them later at school. Only then would I know if my program worked or not, and if not, I had to return home and carefully analyze my code, plus whatever the output was, fix it and then repeat the process the next time I was in front of the computer.

To make it even more frustrating, the terminal was a popular place and there was a long line of other students who wanted to use it as well. The librarian instituted a signup sheet, giving priority to those who wanted to use the career database. John and I convinced her that programming was an equally valid reason to use the computer, so we were next in line, but this still meant we had to show up first thing on the morning that the signup sheet was posted, gaining access to rationed time on an even more rationed and slow computer.

Still, such restricted access had one big benefit: it made us very careful programmers, knowing that a simple error that was prevented at home could save days of computer access later. Most of the time, by the time we entered the programs, they were already so carefully and thoughtfully constructed that they worked the first time, requiring only minor modifications.

The biggest problem was finding out more information about the programming language. The manual in the computer room was too brief to show more than the simplest commands, which we soon outgrew. I thirsted for anything at all that I could do better than John, and soon was scouring every possible source for more information.

One day, hidden in another room at the library I discovered a very thick manual – the real programming manual that had come with the computer but had apparently been forgotten no doubt due to its size and apparent irrelevance. But it wasn’t irrelevant to me. I brought the book home and poured through every page carefully, learning everything I could about seemingly arcane features of the programming language.

Much of my interest was fueled by my rivalry with John, and at first I hid the book from him, only revealing the new commands I uncovered when absolutely necessary to demonstrate some cool new feature. My interest in showing off, of course, soon forced me to reveal the secret manual, which I now shared with John. This proved even better because he soon found more things that I hadn’t seen, and we both became part of a virtuous cycle, getting better and better at programming, at 100 bits per second.

Summer programming

Although summer vacation was of course something all students look forward to, for me especially the end of classes in June meant the end of access to the school’s computer. I think John was less worried about this than I was. Writing computer programs came naturally to him, and although he was as competitive as the next male teenager when it came to trying to outdo me, he had other interests – and skills – besides computers. Summer meant more time for his electronics hobbies, for example, and his father – as owner of a car dealership – had plenty of paid work for him to do as well.

But I was too hooked on this computer to simply go without for the summer. I begged the librarian, a kind and supportive woman named Della Thompson, to let me visit the school during the summer.

Della was the mother of Tracy, a neighbor boy close to Jimbo’s house, a boy we had played with for years. I’d been to his house innumerable times, including once with Jimbo in order to film our own “movie”, a Star Trek wanna-be involving special effects and, of course, interaction with technology and computers. I knew Tracy’s mom from those times at his house, and she knew me as well, so when I finally worked up the nerve to ask for permission to drop by the school, she gladly agreed – at least for the days when she herself was at the school.

To have more access, I needed to speak with Mr. Hoesley, who today would have a title like “IT director”, but in those days was simply an assistant principal, responsible for some of the more mundane tasks that the principal didn’t have time for, like ordering and installing pieces of educational equipment, including the computer in the library.

Mr. Hoesley, fortunately, was happy to have me use the computer in the summer, at least on whatever days the school was open – which was most weekdays, since he himself worked through the summer. Nowadays, somebody like him would be actively involved in the computer education, perhaps writing programs side-by-side with me and John, but he was more than happy to let us do all the computing.

For much of the summer, my daily pattern was similar: ride my bike to the school in time to meet Mr. Hoesley when he arrived and let me in to the library. I’d work there until the day was finished, mostly entering and then debugging computer programs I’d written the night before. If it worked, great! If not, I’d debug as long as I could, and then spend my evening pouring over the printouts to see what had gone wrong, adding and subtracting lines of code until I had a plan for the next day.

I’d also spend evenings pouring through the compute manuals to learn more and more arcane commands, expanding my knowledge of what was possible and learning there was no apparent limit on how cool this technology could be.

TRS-80

It wasn’t until I was in college that some people started to use the term “personal computer” (after the first popular one, the IBM PC). Until then, we called them “home computers” or “microcomputers”. In fact, the “micro” in Microsoft dates from those days, when Bill Gates wanted people to understand that he was making microcomputer software.

These computers were outrageously simple by today’s standards, but that also made them an excellent learning environment because it was possible – just – to understand everything about the entire system, from the chips to software. This made the subject, to me, all the more approachable, and even today I still think about computers in terms that I first understood back then on my first one, the TRS-80.

The TRS-80 came with just one microprocessor, called the Z80. It could execute only a single 8-bit instruction at a time, at the speed of 4.7 kilohertz – just under 5,000 operations per second. By comparison, the PC I use to type this document has eight separate microprocessors, each running about one million times faster and with instructions that are 64-bits. A true comparison isn’t possible, but roughly speaking that’s tens of millions times faster — and my current computer contains many more parts, some of them far more complicated and faster even that that.

My first TRS-80 had a 4K memory RAM memory in which everything had to run, including all graphics on the 64 x 24 line screen. Memory was so tight that the computer didn’t even support lower-case letters; there was a hack to let you display in lower-case, but it required soldering a separate memory chip onto the motherboard, and although I was tempted, I didn’t want to risk ruining the entire computer with a single mistake.

I devoured the manual for the computer, especially the programming guide where I learned about Microsoft BASIC, a simple tiny programing language written by Bill Gates himself and that was actually fairly sophisticated. One of my first add-on purchases was an upgrade to the built-in BASIC, letting me run “Level II” BASIC, a more sophisticated version that ran in 16K. A friend later gave me an even more sophisticated “Level III” version that contained more sophisticated commands and was, at the time, awe-inspiring in its power.

The TRS-80 had a simple architecture, with a single memory space for everything, including graphics and all peripherals. Pressing a key on the keyboard flipped a bit at a fixed place in memory, which you could read in order to tell what was pressed. A major problem, in fact, with the first TRS-80s was that pressing a key prevented the computer from recognizing any other keys until the first was depressed, meaning you had to type very carefully and slowly to avoid missing a character.

It was possible to program the TRS-80 directly in the Z80 machine language, which not only ran much faster, but also gave you more direct control over some of the computer operations. I soon learned how, for example, to write a graphics operation that seemed blindingly fast compared to the built-in BASIC way of doing it. It was also possible to control the output ports and simulate some simple musical tones. Nothing, it seemed, was impossible if you thought cleverly about it.

I learned how to disassemble the built-in BASIC programming language, and I spent hours pouring over the source code, both to learn more how the whole thing operated, but also to teach myself assembly programming. For my sixteenth birthday, I received a Z80 programming manual that soon became among my favorite books; I read every page.

The computer, including monitor, keyboard, and a simple cassette recorder for storing data, cost about $700 (about $2,200 today if you adjust for inflation). That was about half a summer’s earnings for me back then, working at minimum wage.

Although I had played with programming on the timeshare computer at school, nothing compared to the time when I saved up enough money to buy one of my own. I horded magazines to learn more about them, first from our high school library, then from purchases I made during a summer visit to a store in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The key lessons I learned, though, were not so much about programming a computer, but about how approachable the computer could be. Nobody taught me; I just picked up whatever I could from wherever I could, and I learned by trying things.

There is nothing to compare to learning new software ideas by inventing them yourself. That’s how I learned linked lists, for example, or the basics of parsing. When I later learned the “real” algorithms for some of the things I invented myself, it was a huge thrill to see that I already knew this stuff. It was as if I had discovered, independently, a world that was magical and new.

It was this sense, that I could do something that even adults had a hard time with, and that I could master a new domain without a teacher – that sense became deeply ingrained, and was something I never forgot. Years later, when I struggled to learn many other things on my own (the Japanese language, countless other computer programming languages, even new subjects in math or science or biology), I had a special confidence developed long ago in my room in Neillsville, when I learned that passionate focus could turn even a daunting ignorance into mastery.

3.7 Colleges

My parents had attended college – they met at the Eau Claire Teacher’s College, later renamed University of Wisconsin Eau Claire, in the late 1950s – and growing up I heard enough stories that somehow I just assumed I’d be going to college too. It wasn’t a topic of conversation, though. My parents never gave the slightest hint that college was either mandatory or desirable. Ultimately less than half my high school class graduated from college. It wasn’t a big deal one way or another.

School had no appeal to Gary, and he was happy to call his education complete with high school. There were various technical schools that tried to recruit him – welding, electrician, plumber – and I remember one day an army recruiter visiting our house to talk seriously about a career in the military. But he was already making good money at his part-time, now full-time job at the grocery store. The owner (who himself hadn’t attended college) talked seriously about teaching Gary how to run his store someday. Why bother with something as abstract and unnecessary as a college degree when you can live a perfectly good life without the time and expense?

At a church youth group meeting one evening, the subject of discussion was about “who do you admire?”. Whereas I mentioned a famous engineer (Jack Kilby, inventor of the microchip), Gary was more down-to-earth and practical. “Norm Foster”, he replied, speaking of the owner of Neillsville’s hardware store. Mr. Foster was an active member of our church, head of the Neillsville Chamber of Commerce, father of two well-behaved children a few years younger than us. Norm had a college degree – he had been a school teacher in Minneapolis before moving to Neillsville – but it wasn’t obvious that the degree did anything more than cost him tuition money and the time it took away from starting a real business.

Another role model, a church acquaintance who built homes for a living, boasted of the profit he earned – and his goal to become a millionaire by age 30. This seemed far more interesting and doable to my brother than wasting time to get a degree … in what? Gary had no idea what he’d like to study other than some amorphous subject like “business”.

But I liked school, and in sharp contrast with my brother, the small town occupations of store keeper or home builder offered no appeal to me.

My earliest memories of me thinking of adulthood had me at North Central Bible College in Minneapolis, the most respectable school we knew, and rich with first-hand accounts from recent graduates. In those early days when I thought I’d be a missionary, it just seemed natural that I’d be at NCBC.

But later, on a family vacation in Colorado, we stopped at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, which made a big impression on me. Hearing about the intense competition required for admission, I began to understand that there were standards out there far higher than the way I’d calibrated my life to that point. Imagine being in a school where every student was the top of his high school class! I had been interested in airplanes since my hospitalization days, so learning to be an Air Force pilot on the side, at school, seemed like icing on the cake. It was then that I also first heard about the importance of preparation. You don’t just apply to these schools after high school. To stand a chance at admission, I would need a well-rounded academic resume – one that would start in my sophomore year or earlier. Suddenly, high school graduation no longer seemed so distant.

The Air Force Academy tour guide explained how my Freshman and Sophomore years would have a big effect on my application. The others who were applying – my competitors – would have a lengthy list of high school accomplishments, like proven leadership in school clubs. I would need sports credentials too – something in which until then I had no ability, much less interest. Simply showing up wasn’t good enough: I’d need differentiators like maybe a significant statewide first place accomplishment. To top it off, I’d need a Senator’s recommendation, which implied having some experience that would get me some attention.

None of these qualifications would be automatic. My family wouldn’t provide them for me, and nobody at school would tell me what to do. If I wanted to go to the Air Force Academy, I knew, I’d have to figure out all these details on my own. The standardized tests that were required? Nobody had told me what an SAT was – my parents hadn’t heard of it – but that was the least of my worries. I was confident, based on my results on other standardized tests from school, that I’d do pretty well. I needed to know more practical issues, like where the test was offered and how I’d submit my results.

Nothing was urgent, and for that I’m glad that my family made that trip because it started me thinking. Without our visit, I may not have known about highly-selective colleges until much later, when it was no longer possible for me to join the football team or do other activities I wouldn’t have done had I not believed it would help my resume.

It was long after this, in a letter exchange with my friend John Svetlik, that I first heard of Stanford.

3.8 California

Deep in our cold Wisconsin winters, it was easy to dream about life in a place with temperatures that never went below freezing, where it was summertime all year long. But good weather was only one of the many things that appealed to me about California. From my earliest memories of the 60s and their hippies and free-living lifestyle, California was to me always associated with the new, a culture that was slightly ahead of the rest of us.

As for warm climates, most of us had more experience with Florida, which for many people was a winter vacation spot, a place where grandmothers went when they retired, the home of NASA and Disney World. The Gungor family did a roadtrip there one year, bringing back scale models of the Saturn rockets, a physical proof of an exotic but tangible world outside Neillsville. Florida seemed real to me, like Wisconsin only warmer.

California was out of the world, a land beyond, the stuff of legend and myth to me. It also held risks, a place of earthquakes, smog, and of course druggies and sin. My great-grandfather Howard had lived there for a while, and we had relatives still there, though not much direct contact. But overall, there was an over-the-rainbow quality to me of a magic and sometimes scary land that could be explored with a well-prepared adventurous spirit. It was even more special because it seemed like a place for the strong and bold. Anyone could go to Florida, but only a pioneer made it to California.

Sometime in my sophomore or junior year, my parents received a letter from a family in California, announcing that they were considering a move away from the “rat race”, wanting to raise their kids more wholesomely, in farm country far from the city. Central to their choice of location was the existence of a good church, and it seemed we fit the bill.

The Nichols family that arrived was a merger of two families, previously rocked by divorce but now with a happily-married mother and father, with three children from previous marriages: two girls from the mother’s side and a boy from the father’s. The kids were roughly our ages and had apparently been together for so many years that they acted like they’d been family forever. They were all out-going, with sunny personalities that seemed to reflect their homeland, and we immediately became good friends.

The oldest girl was about Gary’s age, and the son was a few years younger, but very easy-going and friendly, and quick to become integrated with all our church activities. The youngest girl was probably about ten or eleven, when I fifteen or sixteen, but she was an excellent flirt around me and I quickly found myself looking forward to every chance we had to meet.

In talking to the Nichols, California suddenly seemed very real to me. It wasn’t a place of mythology, it was a place where people actually lived and grew up. It was also full of the future, of fast highways in exotic Spanish-named cities, with fresh food and a laid-back attitude that made me feel I had found my future home. When they spoke of the shock of the cold Wisconsin winters, I felt a camaraderie.

Soon I acquired a map of the Golden State, which I affixed to the wall of my room and began to memorize the names of the cities, the counties, the rivers. The Nichols were from the small town of Hollister, near Gilroy, famous for its garlic. I looked in wonder at the map, noting how easy it was for them to drive north just a few hours, to magical places like San Jose (just like the song, I remembered, “Do you know the way”).

There was the Central Valley and Salinas, setting of the Steinbeck novels — which of course I eagerly read, absorbing more clues about that magical place.

I saw Highway One winding up the coastline, the famous scenic drive that stretched all the way from South to North, through fresh, coastal beaches and tiny, laid-back surfing towns. As a child of Wisconsin, it would not be until I was eighteen that I first saw an ocean, so the thought of being close to the Pacific brought me a giddy feeling of anticipation, a place I knew I would have to live someday.

It never occurred to me that the Nichols family, despite being long-time California residents exposed to all that Heaven, had for some reason deliberately chose to leave, and to move to – of all places – our small town of Neillsville. If California was so perfect, why on earth would they move?

Mr. Nichols offered an unsatisfying answer. California was too stressful, he said. It was “life in the fast lane”, a place where people drive so fast they can’t look around and enjoy their surroundings. He spoke of freeways full of impatient motorists, scowling when the others move too slowly, raising their fists at each other for no reason other than the constant pressure of living in a land where everything, all the time, had to be new, where the old was tedious and boring, irrelevant.

When he talked about California as a land of high pressure and stress, he might as well have been speaking another language, because to me those words sounded like an invitation to a great, intense, and wonderful game, a place with high stakes and high rewards, of an environment where everyone, all the time, was seeking the future, moving as fast as they could to break out of old molds and old ways of thinking. If that was a little stressful for some people, so be it, I thought. Great things happen to those who work hard. No pain no gain. I knew that I wanted to be part of it.